Tomorrow, February 12th marks exactly two months since my Dad arrived to Guatemala (and two days from which he returns to the States). During his time here, my Dad has been staying at his favored place downtown, Casa Mercedes, just one block from his school, Celas Maya. http://www.celasmaya.edu.gt/ My Dad has enjoyed his stay in Xela so much that he plans on flying south again next winter.

Tomorrow, February 12th marks exactly two months since my Dad arrived to Guatemala (and two days from which he returns to the States). During his time here, my Dad has been staying at his favored place downtown, Casa Mercedes, just one block from his school, Celas Maya. http://www.celasmaya.edu.gt/ My Dad has enjoyed his stay in Xela so much that he plans on flying south again next winter.

The first two weeks of my Dad’s stay in Guatemala began with a vuelt

The first two weeks of my Dad’s stay in Guatemala began with a vuelt a (or trip) de Guatemala and Honduras. After waiting for what Tyler called my Dad’s “adventure travel gear” to arrive from its three-day layover in Houston and for Tyler and I to renew our 3 month visas at immigration in Guatemala City,we hopped on a mini-van for a bumpy, five-hour ride to Copán, Honduras. As a result, my Dad was quickly “broken in” to the luxuries of traveling by crowded private (or public) transportation in Guatemala. The border crossing from Guatemala to Honduras was uneventful and simply required a small payment of 10 quetzales (about $1.30). (The Central America Four agreement allows one to travel across the borders of Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and El Salvador without a visa for each country. This is, of course, very convenient for those travelers just passing through. However, now that Tyler and I have already renewed our visa once in Guatemala City, we’ll be required to head to Mexico or Costa Rica to renew our visas again in March, since the above agreement does not allow for visa renewals within the Central American Four.)

a (or trip) de Guatemala and Honduras. After waiting for what Tyler called my Dad’s “adventure travel gear” to arrive from its three-day layover in Houston and for Tyler and I to renew our 3 month visas at immigration in Guatemala City,we hopped on a mini-van for a bumpy, five-hour ride to Copán, Honduras. As a result, my Dad was quickly “broken in” to the luxuries of traveling by crowded private (or public) transportation in Guatemala. The border crossing from Guatemala to Honduras was uneventful and simply required a small payment of 10 quetzales (about $1.30). (The Central America Four agreement allows one to travel across the borders of Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and El Salvador without a visa for each country. This is, of course, very convenient for those travelers just passing through. However, now that Tyler and I have already renewed our visa once in Guatemala City, we’ll be required to head to Mexico or Costa Rica to renew our visas again in March, since the above agreement does not allow for visa renewals within the Central American Four.) The bruises from our sardine can-ride were quickly forgotten as 15 minutes just past the Honduran border we were met by the very friendly people of the small town Copán Ruinas. We were immediately charmed by the smiling faces of young kids; the cobblestone streets; impressive, tropical plants; red-

The bruises from our sardine can-ride were quickly forgotten as 15 minutes just past the Honduran border we were met by the very friendly people of the small town Copán Ruinas. We were immediately charmed by the smiling faces of young kids; the cobblestone streets; impressive, tropical plants; red- tiled roofs; absence of trash; and excellent food. We immediately decided we’d be staying longer than we had originally planned, just as our guidebook warned might happen.

tiled roofs; absence of trash; and excellent food. We immediately decided we’d be staying longer than we had originally planned, just as our guidebook warned might happen.

The small town of Copán Ruinas is located just a mile from the archeological site of Copán. This “southernmost center of Maya civilization” (Rough Guide to Guatemala) was just a short, pleasant walk down a country road. Upon arriving, we hired a knowledgeable guide to show us around the central part of the massive, 24-square kilometer site. This was the 8th abandoned Mayan city that Tyler has visited, and while the architecture, symbolism and ornamentation have become familiar, Tyler states it has never gotten dull.

We learned that Copán’s location in a long broad valley made it quite suitable as a site to build a city. The small river running through the valley floods during the rainy season and brings nutrients to the flat valley  floor, perfect for growing crops. Also, the two nearby outcroppings of stone in the surrounding hills made for excellent quarries. Sometime around 100 AD construction at Copán began, only later to be abandoned in the 9th century AD. The best guesses as to why the Maya abandoned the city include over development, over-exploitation of resources, and war. (Again, another opportunity for us to learn from history.) If you’re in the neighborhood, Copán is not to be missed.

floor, perfect for growing crops. Also, the two nearby outcroppings of stone in the surrounding hills made for excellent quarries. Sometime around 100 AD construction at Copán began, only later to be abandoned in the 9th century AD. The best guesses as to why the Maya abandoned the city include over development, over-exploitation of resources, and war. (Again, another opportunity for us to learn from history.) If you’re in the neighborhood, Copán is not to be missed.

After our two-day stay in Copan, we returned to Guatemala and headed for the Caribbean Coast. We arrived to the ugly industrial port of Puerto Barrios, the main port from which the United Fruit Company (now Chiquita Banana) exported its goods to the U.S. and the rest of the world. We only stayed in Puerto Barrios

Chiquita Banana) exported its goods to the U.S. and the rest of the world. We only stayed in Puerto Barrios long enough for my Dad to use the restroom at the brothel I accidentally escorted him to and to take the 30 minute ferry ride to Livingston, a coastal town only accessible by boat.

long enough for my Dad to use the restroom at the brothel I accidentally escorted him to and to take the 30 minute ferry ride to Livingston, a coastal town only accessible by boat.

Livingston (population 6,000) is an interesting little town on the Caribbean coast at the mouth of the Río Dulce. As there are no roads connecting Livingston to the rest of the country, all goods must be brought into town in small boats. Unlike Puerto Barrios, there are only low docks that do not allow for large, industrial deliveries. Although there is a minimal road system in the town itself, there is very little motor traffic. A taxi driver told us that there are 80 registered cars in Livingston, as 80 was the limit of car permits the city allows. Pedestrians and bicycles rule the road here. This was definitely our kind of town.

Livingston’s isolated location probably allowed the distinct Garifuna culture of the town to thrive despite being surrounded by the dominant Guatemalan culture. The Garifuna have much more in common wit h Belize and the Caribbean Islands than with Guatemala. The Garifuna are ethnically a mix of African, Carib, and Arawak peoples and their language is today a mix of Arawak, Carib, French, English and Spanish. The Garifuna men and women use distinct dialects of the same language, which may be a result of pre-Columbian ethnic wars in which the males of the losing side were dispatched and the women were taken as captives and later companions by the victors.

h Belize and the Caribbean Islands than with Guatemala. The Garifuna are ethnically a mix of African, Carib, and Arawak peoples and their language is today a mix of Arawak, Carib, French, English and Spanish. The Garifuna men and women use distinct dialects of the same language, which may be a result of pre-Columbian ethnic wars in which the males of the losing side were dispatched and the women were taken as captives and later companions by the victors.

The obvious cultural differences that you see walking around town are the slower pace of life and the music. Reggae, punta, and soka music displace synthesized merengue and traditional marimba ensembles that are ubiquitous in the rest of Guatemala. The main tourist activities in town are eating and chilling out.

While in Livingston, we stayed at a small resort on the sea a couple of kilometers north of town. We took a taxi about three miles from the dock where we arrived to the edge of downtown where the road ends. From there, we walked about a mile along the beach to get to our resort. The resort was composed of a group of several cabins made from lath walls and palm roofs, with a central large open palm roof structure that served as a restaurant and dining room. The first night we unsuccessfully slept through a major offensive launched by the local mosquitoes; however, the second night our mosquito nets acquired from the resort’s caretaker foiled these menaces’ blood-thirsty plans.

Our fi rst day on the beach we spent listening to the rain pound the palm roof of our cabaña, which deafened the sound of the Caribbean Sea lapping on shore just 20 feet in front of us. The following day the clouds broke, the sun filled the sky, and we hiked north along the beach to Siete Altares (Seven Altars). Siete Altares aptly describes a nearby river that runs out over smoothed, limestone rocks, turning into a series of waterfalls and shallow pools. It was a treacherous hike for Tyler as he was barefoot, but even he agreed the gain was worth the pain as you can see from the photos. There were orchids growing on everything and the river was crystal clear.

rst day on the beach we spent listening to the rain pound the palm roof of our cabaña, which deafened the sound of the Caribbean Sea lapping on shore just 20 feet in front of us. The following day the clouds broke, the sun filled the sky, and we hiked north along the beach to Siete Altares (Seven Altars). Siete Altares aptly describes a nearby river that runs out over smoothed, limestone rocks, turning into a series of waterfalls and shallow pools. It was a treacherous hike for Tyler as he was barefoot, but even he agreed the gain was worth the pain as you can see from the photos. There were orchids growing on everything and the river was crystal clear.

As the three of us walked there from our resort, we avoided the crowds that often arrive to Siete Altares by boat together from downtown Livingston. Will, a local who had just moved back from New York, taught us how to climb up the face of the waterfall so we could jump off into its deep, pleasant pool. On our way back from Siete Altares, some of the local Maya kids spotted our camera and asked us to take their pictures.

As the three of us walked there from our resort, we avoided the crowds that often arrive to Siete Altares by boat together from downtown Livingston. Will, a local who had just moved back from New York, taught us how to climb up the face of the waterfall so we could jump off into its deep, pleasant pool. On our way back from Siete Altares, some of the local Maya kids spotted our camera and asked us to take their pictures.

Obviously they have learned from previous tourists that if they stand long enough to pose, they will be awarded with a glimpse of themselves on the playback screen of the digital cameras. I did, however, have to draw a line in the sand to prevent the kids from continually moving too close to the camera’s lens. J I learned this trick from our friends Mark and Bev with whom I sailed to Tonga where we also met enthusiastic local subjects.

In the evening, as the temperature inside our cabaña rose, Tyler and I took our pillows and sheets outside, set up a couple of the resort lounge chairs on the water’s edge and went to sleep to the gentle rolling of the shore onto the beach. We moved back in to our cabaña only as the rain of the days before returned.

The next day we arranged for a boat-taxi to take us from our cabin on the sea back to Livingston. As we were in a very remote location and had spent our last quetzales on breakfast, we notified our “lanchero” that we would have to pay him for the boat ride once we arrived back into town and could get some more money. Once back in Livingston, we learned that there was no cash in either of the two ATMs, that they weren’t expecting any more cash for a couple of days, and our credit cards were useless at the banks but could be used at some restaurants to buy lunch.

The next day we arranged for a boat-taxi to take us from our cabin on the sea back to Livingston. As we were in a very remote location and had spent our last quetzales on breakfast, we notified our “lanchero” that we would have to pay him for the boat ride once we arrived back into town and could get some more money. Once back in Livingston, we learned that there was no cash in either of the two ATMs, that they weren’t expecting any more cash for a couple of days, and our credit cards were useless at the banks but could be used at some restaurants to buy lunch.

As we wondering how we were going to pay the lanchero, Carlos, the Argentinian owner of the jungle eco-resort Finca Tatín, the next resort where we would stay, pulled up to the dock. As he was there to retrieve us, we explained to him our situation, and he quickly lent us the money to pay the lanchero and to get a cup of coffee while he did some grocery shopping before returning to the finca.

As we wondering how we were going to pay the lanchero, Carlos, the Argentinian owner of the jungle eco-resort Finca Tatín, the next resort where we would stay, pulled up to the dock. As he was there to retrieve us, we explained to him our situation, and he quickly lent us the money to pay the lanchero and to get a cup of coffee while he did some grocery shopping before returning to the finca.

Having paid our debt and filled up the small boat with provisions, we all climbed in and turned south up the Río Dulce. Although it began to rain on us in our open “lancha”, we hardly noticed as we were captivated by the numerous birds and 300 feet high, vertical canyon walls that surrounded us as we motored toward the finca. Upon our arrival to Finca Tatín (http://www.fincatatin.centramerica.com/mainE.htm), we immediately knew we were going to like this place. Tyler, my Dad, and I were assigned a comfortable, quaint cabin right on the river’s edge, with a complete bathroom and single bed downstairs for my Dad and a double bed upstairs for me and Tyler. All over the swampy ground of Finca Tatin - around our cabin, around the common areas, etc. - there were thousands of tiny blue crabs slowly crawling around and threatening each other with their 1” long claws.

Having paid our debt and filled up the small boat with provisions, we all climbed in and turned south up the Río Dulce. Although it began to rain on us in our open “lancha”, we hardly noticed as we were captivated by the numerous birds and 300 feet high, vertical canyon walls that surrounded us as we motored toward the finca. Upon our arrival to Finca Tatín (http://www.fincatatin.centramerica.com/mainE.htm), we immediately knew we were going to like this place. Tyler, my Dad, and I were assigned a comfortable, quaint cabin right on the river’s edge, with a complete bathroom and single bed downstairs for my Dad and a double bed upstairs for me and Tyler. All over the swampy ground of Finca Tatin - around our cabin, around the common areas, etc. - there were thousands of tiny blue crabs slowly crawling around and threatening each other with their 1” long claws.

The common area at the resort was filled with hammocks, books for trade, and handmade scrabble, backgammon, and chess boards. The menu listed good, healthy options for breakfast and lunch while dinner was communal, bringing everyone at the resort together at one table. Everything eaten or enjoyed at the resort was based on an honor system.

The common area at the resort was filled with hammocks, books for trade, and handmade scrabble, backgammon, and chess boards. The menu listed good, healthy options for breakfast and lunch while dinner was communal, bringing everyone at the resort together at one table. Everything eaten or enjoyed at the resort was based on an honor system.

The resort kept a book in which each guest had his or her own page where one kept track of one’s meals, drinks, kayak trips, etc. At the end of the stay, one’s total was added and then paid. We added a couple nights stay, a kayak trip to the Biotopo Chocón Machacas (a government protected manatee reserve), and a couple of T-shirts to our tab before moving on up river to the town of Río Dulce. The town of Río Dulce wasn’t much more than a crossroads where we withdrew money from the ATM to pay our hosts on the river and catch our bus n

The resort kept a book in which each guest had his or her own page where one kept track of one’s meals, drinks, kayak trips, etc. At the end of the stay, one’s total was added and then paid. We added a couple nights stay, a kayak trip to the Biotopo Chocón Machacas (a government protected manatee reserve), and a couple of T-shirts to our tab before moving on up river to the town of Río Dulce. The town of Río Dulce wasn’t much more than a crossroads where we withdrew money from the ATM to pay our hosts on the river and catch our bus n orthwest to the town of Flores, seven hours away.

orthwest to the town of Flores, seven hours away.

Flores, the town nearest to Tikal, the most important ancient Maya site in Guatemala, is a touristy but cute little town built on an island in Lake Petén Itzá. The town is basically looped by one cobblestone street and is connected to the mainland by a human-made bridge. The cobbled streets are clean, the restaurants generally decent, the motor traffic minimal, the people friendly, and there’s always a view of the lake. We were still dealing with a shortage of cash  as we quickly learned there were no ATM machines in Flores, and those ATMs in Santa Elena, the town on the other side of the bridge, did not contain any cash. However, we got lucky when an armored car arrived as we were standing outside the third bank we tried and the ATM was restocked. After withdrawing as much as we could, we returned to our pleasant, air-conditioned rooms.

as we quickly learned there were no ATM machines in Flores, and those ATMs in Santa Elena, the town on the other side of the bridge, did not contain any cash. However, we got lucky when an armored car arrived as we were standing outside the third bank we tried and the ATM was restocked. After withdrawing as much as we could, we returned to our pleasant, air-conditioned rooms.

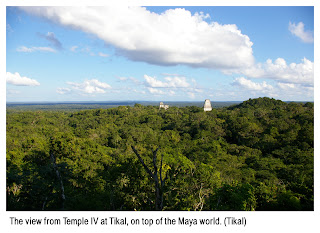

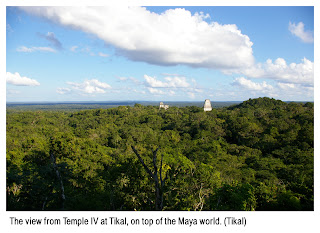

On our second day in Flores, my Dad took the day off and chilled out in town while Tyler and I took a hired sardine  can/mini-van to Tikal. We got there relatively late in the afternoon, found a guide, and took an express tour of the ruins. We got really lucky with our guide, who grew up just a few miles from Tikal in Uaxactún (sounds like Wa-shing-ton, seriously), and was extremely knowledgeable in medicinal plants, botany, biology, and local history. Our late arrival turned out to have an advantage; there were no tourists to distract our enjoyment of the park. We climbed several pyramids to find that we were the only ones on the structure. The views from the tops of the pyramids were spectacular, and the forest was busy with spider monkeys, parakeets, parrots, wild turkeys, oropendolas, woodpeckers, brown jays, hummingbirds, and much more. We saw many groups of leaf cutter ants carrying little green flags across the footpaths. The ants put their leafy treasures into fermenting holes and later eat the fungus that grows on the rotting leaves. We learned from our guide that these ants are basically mushroom farmers.

can/mini-van to Tikal. We got there relatively late in the afternoon, found a guide, and took an express tour of the ruins. We got really lucky with our guide, who grew up just a few miles from Tikal in Uaxactún (sounds like Wa-shing-ton, seriously), and was extremely knowledgeable in medicinal plants, botany, biology, and local history. Our late arrival turned out to have an advantage; there were no tourists to distract our enjoyment of the park. We climbed several pyramids to find that we were the only ones on the structure. The views from the tops of the pyramids were spectacular, and the forest was busy with spider monkeys, parakeets, parrots, wild turkeys, oropendolas, woodpeckers, brown jays, hummingbirds, and much more. We saw many groups of leaf cutter ants carrying little green flags across the footpaths. The ants put their leafy treasures into fermenting holes and later eat the fungus that grows on the rotting leaves. We learned from our guide that these ants are basically mushroom farmers.

Our third day in Peten (the northern Guatemalan state or “department” where Flores and Tikal are located) was spent visiting Ixpanpajul, an overpriced park with suspension footbridges and tree canopy excursions located not too far from Flores. The staff at the park keeps the paths in good condition, and the long suspension bridges offer nice views of the park and surrounding area, but we felt the $25 entrance fee per person was a bit steep for a hike through foliage similar to that found at Tikal. While Ixpanpajul did offer the sounds of howler monkeys miles off in the trees, it lacked the magnificence of the ruins and flora and fauna of Tikal, for which we paid the equivalent of $7.00 each. On our way out of the park, I politely told the woman at the front desk about our disappointment at being charged so much for so little.

Our third day in Peten (the northern Guatemalan state or “department” where Flores and Tikal are located) was spent visiting Ixpanpajul, an overpriced park with suspension footbridges and tree canopy excursions located not too far from Flores. The staff at the park keeps the paths in good condition, and the long suspension bridges offer nice views of the park and surrounding area, but we felt the $25 entrance fee per person was a bit steep for a hike through foliage similar to that found at Tikal. While Ixpanpajul did offer the sounds of howler monkeys miles off in the trees, it lacked the magnificence of the ruins and flora and fauna of Tikal, for which we paid the equivalent of $7.00 each. On our way out of the park, I politely told the woman at the front desk about our disappointment at being charged so much for so little.

Our next destination from Peten was the old colonial city (and former capital of Guatemala) Antigua, about 45 minutes outside Guatemala City. We had two options for making the trip to Antigua: 1. Take a 9.5-hour bus ride from Flores to Guatemala City, then a shuttle to Antigua, or 2. Take a 1-hour plane ride (for about $100.00) from Flores to Guatemala City, and then a shuttle to Antigua. It didn’t take long to make that decision. We flew at night and the whole country was dark; only a few times were there a few lines of dim street lights indicating a village below.

Our next destination from Peten was the old colonial city (and former capital of Guatemala) Antigua, about 45 minutes outside Guatemala City. We had two options for making the trip to Antigua: 1. Take a 9.5-hour bus ride from Flores to Guatemala City, then a shuttle to Antigua, or 2. Take a 1-hour plane ride (for about $100.00) from Flores to Guatemala City, and then a shuttle to Antigua. It didn’t take long to make that decision. We flew at night and the whole country was dark; only a few times were there a few lines of dim street lights indicating a village below.  Suddenly we came over a mountain range and the orange-yellow lights of Guatemala’s capital spread out to the horizon. We arrived at our hotel in Antigua, an elegant colonial style building with a courtyard and garden, at about 11 pm and quickly went to sleep, dreaming of the next day’s adventures.

Suddenly we came over a mountain range and the orange-yellow lights of Guatemala’s capital spread out to the horizon. We arrived at our hotel in Antigua, an elegant colonial style building with a courtyard and garden, at about 11 pm and quickly went to sleep, dreaming of the next day’s adventures.

We woke up in Antigua on Dec 24th, had our complimentary breakfast, and took a stroll around town. Our only plan for the day was to find the best coffee and pastries in town, an admirable goal for which Tyler happily takes credit. As it turned out, Christmas Eve was not the  best day for pastry hunting as many shops were closed; however, we were able to find some acceptable cheesecake and cappuccinos.

best day for pastry hunting as many shops were closed; however, we were able to find some acceptable cheesecake and cappuccinos.

On Christmas Day we had lunch at the Swiss owned Mesón Panza Verde. The three of us agreed that this was the most significant culinary experience we’d had in a long time. Tyler tried to take note of all the subtle and perfectly balanced flavors so he could try and recreate them later in his tiny kitchen in Xela. Beginning with our incredible arugula salads with a homemade dressing,  we knew we were in for a culinary treat. My Dad and I went for the traditional turkey dinner with mashed potatoes– the best I’ve ever had (sorry mom!). Tyler had salmon with baked squash and yams. We were in ecstasy all the way through to the arrival of our chocolate mousse and apple streudel desserts, and even then we were not disappointed.

we knew we were in for a culinary treat. My Dad and I went for the traditional turkey dinner with mashed potatoes– the best I’ve ever had (sorry mom!). Tyler had salmon with baked squash and yams. We were in ecstasy all the way through to the arrival of our chocolate mousse and apple streudel desserts, and even then we were not disappointed.

As we walked off our lunch around town, we happened upon a Christmas parade. We were enjoying the antics of the masked parade-goers and marimba players so much that we followed them for a couple of blocks. Later in the evening, Tyler and I went out in search of dessert and came upon a fusion Thai restaurant called Café Flor. We enjoyed the live piano music that was playing, but I was a little put off by my chocolate brownie made from corn flour, and we were both put off by the host/pianist’s peddling of music CDs at our table when the bill came.

On December 26th, we headed back to Xela from Antigua by bus. We were glad to see the landscape change to pine trees and feel the air change to the cool mountain climate of the Western Highlands. After two-weeks traveling around Honduras and Guatemala, we were happy to be back at our home away from home.

On December 26th, we headed back to Xela from Antigua by bus. We were glad to see the landscape change to pine trees and feel the air change to the cool mountain climate of the Western Highlands. After two-weeks traveling around Honduras and Guatemala, we were happy to be back at our home away from home.

The first two weeks of my Dad’s stay in

The first two weeks of my Dad’s stay in  a (or trip) de

a (or trip) de  The bruises from our sardine can-ride were quickly forgotten as 15 minutes just past the Honduran border we were met by the very friendly people of the small town Copán Ruinas. We were immediately charmed by the smiling faces of young kids; the cobblestone streets; impressive, tropical plants; red-

The bruises from our sardine can-ride were quickly forgotten as 15 minutes just past the Honduran border we were met by the very friendly people of the small town Copán Ruinas. We were immediately charmed by the smiling faces of young kids; the cobblestone streets; impressive, tropical plants; red- tiled roofs; absence of trash; and excellent food. We immediately decided we’d be staying longer than we had originally planned, just as our guidebook warned might happen.

tiled roofs; absence of trash; and excellent food. We immediately decided we’d be staying longer than we had originally planned, just as our guidebook warned might happen.  floor, perfect for growing crops. Also, the two nearby outcroppings of stone in the surrounding hills made for excellent quarries. Sometime around 100 AD construction at Copán began, only later to be abandoned in the 9th century AD. The best guesses as to why the Maya abandoned the city include over development, over-exploitation of resources, and war. (Again, another opportunity for us to learn from history.) If you’re in the neighborhood, Copán is not to be missed.

floor, perfect for growing crops. Also, the two nearby outcroppings of stone in the surrounding hills made for excellent quarries. Sometime around 100 AD construction at Copán began, only later to be abandoned in the 9th century AD. The best guesses as to why the Maya abandoned the city include over development, over-exploitation of resources, and war. (Again, another opportunity for us to learn from history.) If you’re in the neighborhood, Copán is not to be missed.

Chiquita Banana) exported its goods to the

Chiquita Banana) exported its goods to the  long enough for my Dad to use the restroom at the brothel I accidentally escorted him to and to take the 30 minute ferry ride to Livingston, a coastal town only accessible by boat.

long enough for my Dad to use the restroom at the brothel I accidentally escorted him to and to take the 30 minute ferry ride to Livingston, a coastal town only accessible by boat.  h Belize and the Caribbean Islands than with Guatemala. The Garifuna are ethnically a mix of African, Carib, and Arawak peoples and their language is today a mix of Arawak, Carib, French, English and Spanish. The Garifuna men and women use distinct dialects of the same language, which may be a result of pre-Columbian ethnic wars in which the males of the losing side were dispatched and the women were taken as captives and later companions by the victors.

h Belize and the Caribbean Islands than with Guatemala. The Garifuna are ethnically a mix of African, Carib, and Arawak peoples and their language is today a mix of Arawak, Carib, French, English and Spanish. The Garifuna men and women use distinct dialects of the same language, which may be a result of pre-Columbian ethnic wars in which the males of the losing side were dispatched and the women were taken as captives and later companions by the victors.  rst day on the beach we spent listening to the rain pound the palm roof of our cabaña, which deafened the sound of the Caribbean Sea lapping on shore just 20 feet in front of us. The following day the clouds broke, the sun filled the sky, and we hiked north along the beach to Siete Altares (Seven Altars). Siete Altares aptly describes a nearby river that runs out over smoothed, limestone rocks, turning into a series of waterfalls and shallow pools. It was a treacherous hike for

rst day on the beach we spent listening to the rain pound the palm roof of our cabaña, which deafened the sound of the Caribbean Sea lapping on shore just 20 feet in front of us. The following day the clouds broke, the sun filled the sky, and we hiked north along the beach to Siete Altares (Seven Altars). Siete Altares aptly describes a nearby river that runs out over smoothed, limestone rocks, turning into a series of waterfalls and shallow pools. It was a treacherous hike for  As the three of us walked there from our resort, we avoided the crowds that often arrive to Siete Altares by boat together from downtown

As the three of us walked there from our resort, we avoided the crowds that often arrive to Siete Altares by boat together from downtown

The next day we arranged for a boat-taxi to take us from our cabin on the sea back to

The next day we arranged for a boat-taxi to take us from our cabin on the sea back to  As we wondering how we were going to pay the lanchero, Carlos, the Argentinian owner of the jungle eco-resort Finca Tatín, the next resort where we would stay, pulled up to the dock. As he was there to retrieve us, we explained to him our situation, and he quickly lent us the money to pay the lanchero and to get a cup of coffee while he did some grocery shopping before returning to the finca.

As we wondering how we were going to pay the lanchero, Carlos, the Argentinian owner of the jungle eco-resort Finca Tatín, the next resort where we would stay, pulled up to the dock. As he was there to retrieve us, we explained to him our situation, and he quickly lent us the money to pay the lanchero and to get a cup of coffee while he did some grocery shopping before returning to the finca. Having paid our debt and filled up the small boat with provisions, we all climbed in and turned south up the Río Dulce. Although it began to rain on us in our open “lancha”, we hardly noticed as we were captivated by the numerous birds and 300 feet high, vertical canyon walls that surrounded us as we motored toward the finca. Upon our arrival to Finca Tatín (http://www.fincatatin.centramerica.com/mainE.htm), we immediately knew we were going to like this place. Tyler, my Dad, and I were assigned a comfortable, quaint cabin right on the river’s edge, with a complete bathroom and single bed downstairs for my Dad and a double bed upstairs for me and Tyler. All over the swampy ground of Finca Tatin - around our cabin, around the common areas, etc. - there were thousands of tiny blue crabs slowly crawling around and threatening each other with their 1” long claws.

Having paid our debt and filled up the small boat with provisions, we all climbed in and turned south up the Río Dulce. Although it began to rain on us in our open “lancha”, we hardly noticed as we were captivated by the numerous birds and 300 feet high, vertical canyon walls that surrounded us as we motored toward the finca. Upon our arrival to Finca Tatín (http://www.fincatatin.centramerica.com/mainE.htm), we immediately knew we were going to like this place. Tyler, my Dad, and I were assigned a comfortable, quaint cabin right on the river’s edge, with a complete bathroom and single bed downstairs for my Dad and a double bed upstairs for me and Tyler. All over the swampy ground of Finca Tatin - around our cabin, around the common areas, etc. - there were thousands of tiny blue crabs slowly crawling around and threatening each other with their 1” long claws. The common area at the resort was filled with hammocks, books for trade, and handmade scrabble, backgammon, and chess boards. The menu listed good, healthy options for breakfast and lunch while dinner was communal, bringing everyone at the resort together at one table. Everything eaten or enjoyed at the resort was based on an honor system.

The common area at the resort was filled with hammocks, books for trade, and handmade scrabble, backgammon, and chess boards. The menu listed good, healthy options for breakfast and lunch while dinner was communal, bringing everyone at the resort together at one table. Everything eaten or enjoyed at the resort was based on an honor system. The resort kept a book in which each guest had his or her own page where one kept track of one’s meals, drinks, kayak trips, etc. At the end of the stay, one’s total was added and then paid. We added a couple nights stay, a kayak trip to the Biotopo Chocón Machacas (a government protected manatee reserve), and a couple of T-shirts to our tab before moving on up river to the town of

The resort kept a book in which each guest had his or her own page where one kept track of one’s meals, drinks, kayak trips, etc. At the end of the stay, one’s total was added and then paid. We added a couple nights stay, a kayak trip to the Biotopo Chocón Machacas (a government protected manatee reserve), and a couple of T-shirts to our tab before moving on up river to the town of  orthwest to the town of

orthwest to the town of  as we quickly learned there were no ATM machines in

as we quickly learned there were no ATM machines in  can/mini-van to

can/mini-van to  Our third day in Peten (the northern Guatemalan state or “department” where

Our third day in Peten (the northern Guatemalan state or “department” where  Our next destination from Peten was the old colonial city (and former capital of

Our next destination from Peten was the old colonial city (and former capital of  Suddenly we came over a mountain range and the orange-yellow lights of

Suddenly we came over a mountain range and the orange-yellow lights of  best day for pastry hunting as many shops were closed; however, we were able to find some acceptable cheesecake and cappuccinos.

best day for pastry hunting as many shops were closed; however, we were able to find some acceptable cheesecake and cappuccinos.  we knew we were in for a culinary treat. My Dad and I went for the traditional turkey dinner with mashed potatoes– the best I’ve ever had (sorry mom!).

we knew we were in for a culinary treat. My Dad and I went for the traditional turkey dinner with mashed potatoes– the best I’ve ever had (sorry mom!).  On December 26th, we headed back to Xela from

On December 26th, we headed back to Xela from