rts, working with teachers and administration on testing students and placing them into levels, evaluating and choosing student textbooks, and facilitating teacher trainer workshops. My office is downtown at IGA-Sede (http://www.igaxela.org) . (Sede means central seat or office.) Here classes are offered in the mornings before work or school from

rts, working with teachers and administration on testing students and placing them into levels, evaluating and choosing student textbooks, and facilitating teacher trainer workshops. My office is downtown at IGA-Sede (http://www.igaxela.org) . (Sede means central seat or office.) Here classes are offered in the mornings before work or school from The building where IGA-Sede is located used to be a private house and then a hotel. The rooms are arranged around a central courtyard, as is typical in Spanish architecture. Saturdays are the busiest days at IGA when both university students and elementary kids come to study for 3-6 hours. Therefore, most of the teachers at IGA Sede teach six days a week. I only go in on Saturdays when I have to observe. Having the weekend off is one of my cultural customs I’m clingin

g on to.

g on to.Although IGA-Sede is non-denominational, it coordinates and runs the English programs at two local Catholic schools: Liceo Guatemala, the boys Catholic school, and Maria Auxiliadora, the girls Catholic School. Both schools are Kindergarten through twelfth grade with the 10-12th graders specializing in a profession. The boys are offered careers in Computation, Graphic Design, Medicine, and Sciences. The girls are offered a career in…being bilingual secretaries. IGA-Sede is currently working on getting a teaching program for the girls approved by the Ministry of Education; however, it is currently an uphill battle.  Of course other options are available to both male and female students if they study in a bachillerato or college prep program and continue on to college.

Of course other options are available to both male and female students if they study in a bachillerato or college prep program and continue on to college.

I don’t work so much with students but spend most of my time with the teachers. They are a really great, hard-working group, most of them teaching both at IGA-Sede and in the Liceo and Maria programs. Brenda, the Director of IGA-Xela (which includes Sede, Liceo, and Maria), was a Fulbright scholar in the States and has a background in non-governmental organization (NGO) administration. Before directing IGA-Xela (a non-profit organization), she was both a teacher and worked for the NGO Save the Children. She runs her programs very professionally and, at the same time, treats her faculty and staff like family. I have told Brenda that I feel as if I have won the English Language Fellow lottery, having been placed under her direction. Needless to say, I am really enjoying my job.

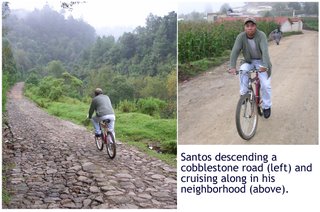

Play: As one can note from his previous posting, Tyler’s mission in life here  is to find the best mountain biking trail and something more diverse to eat. Just recently Tyler participated in a night race, 4km (about 3 miles) almost all up a steep slope. He has become a familiar fixture at the local bike shops. Tyler also scored for us yesterday when he bought a 2 pound bottle of Tahini from the local restaurant owner of Café Babylon. Tyler has been a big support to me both at home and at work. This week we team facilitated a workshop on Teaching Grammar in Context.

is to find the best mountain biking trail and something more diverse to eat. Just recently Tyler participated in a night race, 4km (about 3 miles) almost all up a steep slope. He has become a familiar fixture at the local bike shops. Tyler also scored for us yesterday when he bought a 2 pound bottle of Tahini from the local restaurant owner of Café Babylon. Tyler has been a big support to me both at home and at work. This week we team facilitated a workshop on Teaching Grammar in Context.

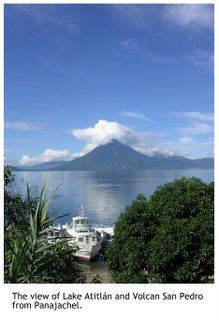

The weekend of October 7th Tyler and I finally took a trip out of town to Panajachel (Pahn-ah-ha-chell) with an American, Scott, who works at IGA-Sede and who has been living in Xela for the past seven years. Panajachel is a small village located on the beautiful Lake Atitlán, about a four-hour trip on one of the local chicken buses if the road is clear. (Hurricane Stan caused a lot of damage last year, so bridges are being built where roads were washed away.) P anajachel was once populated by the Tz’utujil until they were defeated by a rival Maya group, the Kaqchikel, with the help of the Spanish conquistadors. Panajachel is a quaint little town with cobblestone streets, but it has long been discovered by gringos. Therefore, much of the businesses along the main drag pander to foreign tourists. As a result, the spectacular views of Lake Atitlán and the surrounding volcanoes are somewhat spoiled by aggressive locals selling their wares and services.

anajachel was once populated by the Tz’utujil until they were defeated by a rival Maya group, the Kaqchikel, with the help of the Spanish conquistadors. Panajachel is a quaint little town with cobblestone streets, but it has long been discovered by gringos. Therefore, much of the businesses along the main drag pander to foreign tourists. As a result, the spectacular views of Lake Atitlán and the surrounding volcanoes are somewhat spoiled by aggressive locals selling their wares and services.

Lake Atitlán is a spectacular sight; however, it has faced it's own share of environmental degradation. One of the islands the lake surrounds is a nature preserve to protect the local species of grebe from extinction as the island consists of reeds that are necessary for the birds' survival. Unfortunately, however, with the introduction of black bass not native to the lake's ecosystem, the birds were unable to avoid their tragic fate as the carnivorous fish feasted on the small grebe offspring.

Panajachel and the villages of Lake Atitlan are the first places we have seen where Maya men still wear the clothes of their ancestors. Due to the prejudice against the Maya, many Maya men who had to deal with their European brethren found it easier to do business if they succumbed to wearing the clothes of westerners. However, many Maya women in both the larger cities and smaller villages honor their traditional heritage by weaving and wearing the multi-colored huipil (blouse) and corte (woven wraparound skirt), the skill of which has been passed down through hundreds of years. Maya men and women wear only the colors and patterns of textiles that represent the region where they are from.

The central plaza in Santiago Atitlan is a meeting place for both young and old. The plaza is where you'll find the local shool, church, and market. It is the cultural center of town.

A common sight in the streets of towns and cities in Guatemala is the large loads Maya women car ry on their heads to and from the market. I never cease to be impressed by how much they can balance on their heads.

ry on their heads to and from the market. I never cease to be impressed by how much they can balance on their heads.

Keeping one's shoes cleaned and shined is a serious business in Guatemala. Most of the shoeshiners are young boys who will offer their services for 2 or 3 quetzales (about 30-40 cents). It's somewhat controversial engaging in commerce with such a young person for their are two sides to the coin. On  the one hand, by taking advantage of his services you could be supplying the shoeshiner with much needed quetzales in order to get something to eat. On the other hand, one wonders if one isn't encouraging him to stay in the streets to make his living (rather than going to school) and encouraging his parents to send him out into the street to earn for his family.

the one hand, by taking advantage of his services you could be supplying the shoeshiner with much needed quetzales in order to get something to eat. On the other hand, one wonders if one isn't encouraging him to stay in the streets to make his living (rather than going to school) and encouraging his parents to send him out into the street to earn for his family.

Our afternoon in Santiago Atitlán ended with the 20-minute boat ride back across the lake to Panajachel. Our small lancha was occupied by Americans, Europeans, and a few Maya locals. The Europeans shared with everyone the small, sweet bananas they had just bought, and I couldn't help thinking how such large cultural and language barriers can so simply be crossed with a piece of fruit. Of course the irony is how much conflict was also brought to the country of Guatemala over bananas. Anyone who has studied the history of Guatmala, especially the years  which led up to the bloody civil war only 10 years past, knows what a significant role the United States played in Guatemala's very recent conflict.

which led up to the bloody civil war only 10 years past, knows what a significant role the United States played in Guatemala's very recent conflict.

United Fruit Company: In 1931 Jorge Ubico was elected president of Guatemala. According to Maureen Shea's Culture and Customs of Guatemala (2001), for thirteen years he ruled "with an iron hand...tolerating no dissent." Paraphrasing Shea, Ubico was able to keep the Guatemalan economy from total collapse by courting, largely, US investors and through exploiting the Maya people as a labor force. In order to maintain power, Ubico continued to grant US investors, particularly the United Fruit Company, with the most fertile lands, lands that were often already being cultivated by Maya, in return for US support of his "illegal, fixed reelections" (ibid). Ubico permitted the United Fruit Company to continue to exploit the Maya workforce and made the company exempt from import duties and property taxes. Nine years after Ubico's first election, 90 percent of Guatemala's produce was being sold directly to the US. During World War II, as many educated Guatemalans became aware of the ideals of freedom being espoused by the US, many students protested and were joined in a strike by laborers during the October Revolution. As a result, in 1944, Ubico, the largest landowner in Guatemala, was forced to resign.

import duties and property taxes. Nine years after Ubico's first election, 90 percent of Guatemala's produce was being sold directly to the US. During World War II, as many educated Guatemalans became aware of the ideals of freedom being espoused by the US, many students protested and were joined in a strike by laborers during the October Revolution. As a result, in 1944, Ubico, the largest landowner in Guatemala, was forced to resign.

The period from 1944-1954 following Ubico's resignation is known as "The Ten Years of Spring". A provisional government run by two military officers and a civilian governed until Juan Jose Arevalo, a progressive, was elected, largely with the help of student support. Although Arevalo brought about reform in literacy and voting rights, it was not until his successor Arbenz Guzman, elected in 1950, was the issue of land reform addressed.

In order to decrease Guatemala's economic reliance on the US and bananas and in order to improve the conditions of the Maya people, Guzman "attempted to diversify crop production and establish alternative institutions to compete with those that United Fruit dominated" (ibid). In 1952, the Guatemalan government passed into law the Law of Agrarian Reform which called for the redistribution of unused or underutilized land to the landless Maya people. "Lands that were to be redistributed were public lands, those that were not farmed or those in excess of 488 acres, with exceptions made for those that were efficiently farmed" (ibid). The elite landowners saw this as a threat to their wealth and power, as did the United Fruit Company which only utilized 15 percent of its landholdings. Also, the Board of Directors of United Fruit were "angered by the provision that the value of their land would be determined by what they had reported for tax purposes, since they had misrepresented this value for years" (ibid) and that they were required to pay $10.5 million in back taxes for the International Railway Company in operation in Guatemala, a branch of United Fruit. As a result, the United Fruit Company began a smear campaign in the United States during the McCarthy era and labeled Guzman and his government as communist. John Foster Dulles, then US Secretary of State, and his brother Allen Dulles, then head of the CIA, had close ties to the United Fruit Company, and they were able to persuad e President Eisenhower that United Fruit was "being victimized by the communist regime in Guatemala" (ibid). The Catholic church in Guatemala, itself a landowner and ally to the landowners and conservatives who supported the clergy, also protested the land reform measure and cried 'communism'. "In short, the Catholic Church, the United Fruit Company, and the US governement formed a powerful alliance and began to pressure the military" (ibid) which resulted in a CIA-led military coup in 1954 of a democratically elected president, ending the "Ten Years of Spring". Guzman was replaced by Castillo Armas who led the invading forces into Guatemala City and who, shortly thereafter, "annulled the 1945 Constitution, did away with the Law of Agrarian Reform and returned the expropriated lands" (ibid). Shea has named the period that followed the coup the "Era of Darkness" from which arose the bloody Guatemalan civil war that would last until 1996. One cannot help wonder what life would be like now for Guatemala, especially for the Maya, if the reforms Guzman had put into place had been allowed to stand. It sure makes once think twice about buying bananas from United Fruit Company, now known as Chiquita.

e President Eisenhower that United Fruit was "being victimized by the communist regime in Guatemala" (ibid). The Catholic church in Guatemala, itself a landowner and ally to the landowners and conservatives who supported the clergy, also protested the land reform measure and cried 'communism'. "In short, the Catholic Church, the United Fruit Company, and the US governement formed a powerful alliance and began to pressure the military" (ibid) which resulted in a CIA-led military coup in 1954 of a democratically elected president, ending the "Ten Years of Spring". Guzman was replaced by Castillo Armas who led the invading forces into Guatemala City and who, shortly thereafter, "annulled the 1945 Constitution, did away with the Law of Agrarian Reform and returned the expropriated lands" (ibid). Shea has named the period that followed the coup the "Era of Darkness" from which arose the bloody Guatemalan civil war that would last until 1996. One cannot help wonder what life would be like now for Guatemala, especially for the Maya, if the reforms Guzman had put into place had been allowed to stand. It sure makes once think twice about buying bananas from United Fruit Company, now known as Chiquita.